Beyond Treatment: Expecting More From Your Follow-Up Care

Updated on November 14, 2024

In the U.S., there are more than 4 million people with a history of breast cancer. Many of them are dealing with long-lasting physical and emotional effects of their treatment.

Follow-up care after active treatment is supposed to address their ongoing needs — managing treatment side effects, checking for the cancer coming back, and coordinating care among providers. But people often struggle to access appropriate follow-up care after active treatment.

In this Breastcancer.org special report, we investigate the barriers that prevent people from getting the care and support they need after they finish their initial treatments for breast cancer and the steps you can take to find follow-up care that helps you heal and move forward.

For a few months after she completed her main treatments for breast cancer — chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation — in 2016, Megan-Claire Chase felt a joyous sense of relief. “The hair I lost during chemo was starting to grow back, and I was happy that I was still here — that I was alive,” she says. When she returned to her office in Atlanta, Georgia, after taking time off from work to recover from surgery, she was surprised and touched to see that her co-workers had covered her desk in cards and presents.

Soon after, Chase had an appointment with her oncologist to discuss her transition to follow-up care. She knew she would be seeing her oncologist less often once her main treatment was finished — just once every few months. But she was disappointed that she wasn’t given any resources or information about what might come next: symptoms to watch out for that could signal a return of cancer, possible side effects from the treatments she received, or a referral to counseling to help her process what she’d been through.

“I was handed a folder with one sheet of paper that just had information on my diagnosis and treatments, and where I was treated — that’s it. I was kind of tossed out there with no support,” she says. “It was like: ‘We did our job because you’re not dead. Now we’ve got to move on to the next person.’”

Over time, Chase, who is now the early-stage breast cancer program director at SHARE Cancer Support, realized that she wasn’t healing the way she expected to. She suffered from several long-term treatment complications, including severe chemo-induced peripheral neuropathy (causing numbness in her hands and feet) and brain fog that made it difficult for her to work.

“No one prepared me that my quality of life wouldn’t come back. That was a big letdown,” she says. She eventually found some therapies for the side effects on her own, without much help from her cancer treatment team.

“There isn’t enough help for people in the survivorship stage, when they have all these health problems they never would have had if it wasn’t for the cancer treatment,” she says. “We’re just thrown out into the middle of the ocean with a life jacket that is not fully inflated and we’re struggling to stay afloat.”

The end of treatment and the transition to follow-up care

People who, like Chase, have been diagnosed with early-stage or locally advanced (non-metastatic) breast cancer typically complete their initial treatments — such as surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy — and then start receiving follow-up (or “survivorship”) care. (Those diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer — cancer that has spread to other parts of the body — usually stay in active treatment for the rest of their lives and so don’t transition to follow-up care.)

In this follow-up care phase, people might still be receiving long-term treatments such as hormonal therapy, but visits with their cancer care team become less frequent. The focus of their care usually shifts to monitoring their overall health and well-being and checking for recurrence (the cancer returning).

However, while this period is less intensive than the active treatment phase in terms of doctor’s visits, tests, and treatments, it’s not the end of the cancer journey. People finishing up active treatment are facing risks and challenges they wouldn’t have if they hadn’t been diagnosed with breast cancer.

They have a risk of the cancer returning.

They have a higher risk of developing a new breast cancer than someone who never had a breast cancer diagnosis.

Depending on the treatments they received, they may be at a higher risk for conditions such as heart disease, osteoporosis, infertility, and some other types of cancer.

They’re also at risk for other long-term side effects from treatment, mental health problems, and financial problems related to their treatment.

Getting comprehensive, well-coordinated follow-up care matters because it can help prevent, minimize, or address these problems.

For many people, though, the transition to follow-up care is a disorienting time filled with mixed emotions. They may feel relieved to put treatment behind them, but nervous about seeing their oncologist less often or worried about their risk of recurrence. They may not know how to resume the parts of their lives that they’d put on hold. They may wonder how to manage the changes to their body, mind, identity, relationships, work, and finances.

Add to this the fact that follow-up care guidelines may be confusing. Some people aren’t given a clear plan for the next steps in their cancer care, leading to uncertainty around which health care providers to see for their care, how often to see them, and which ongoing tests or screenings they need. As a result, many breast cancer survivors aren’t accessing follow-up care that meets their needs.

A 2023 Breastcancer.org survey of 995 people who live in the United States and were diagnosed with breast cancer in the past 10 years found that:

While the majority of respondents were satisfied, a substantial minority (35%) felt either unsatisfied with or neutral about their post-treatment survivorship care

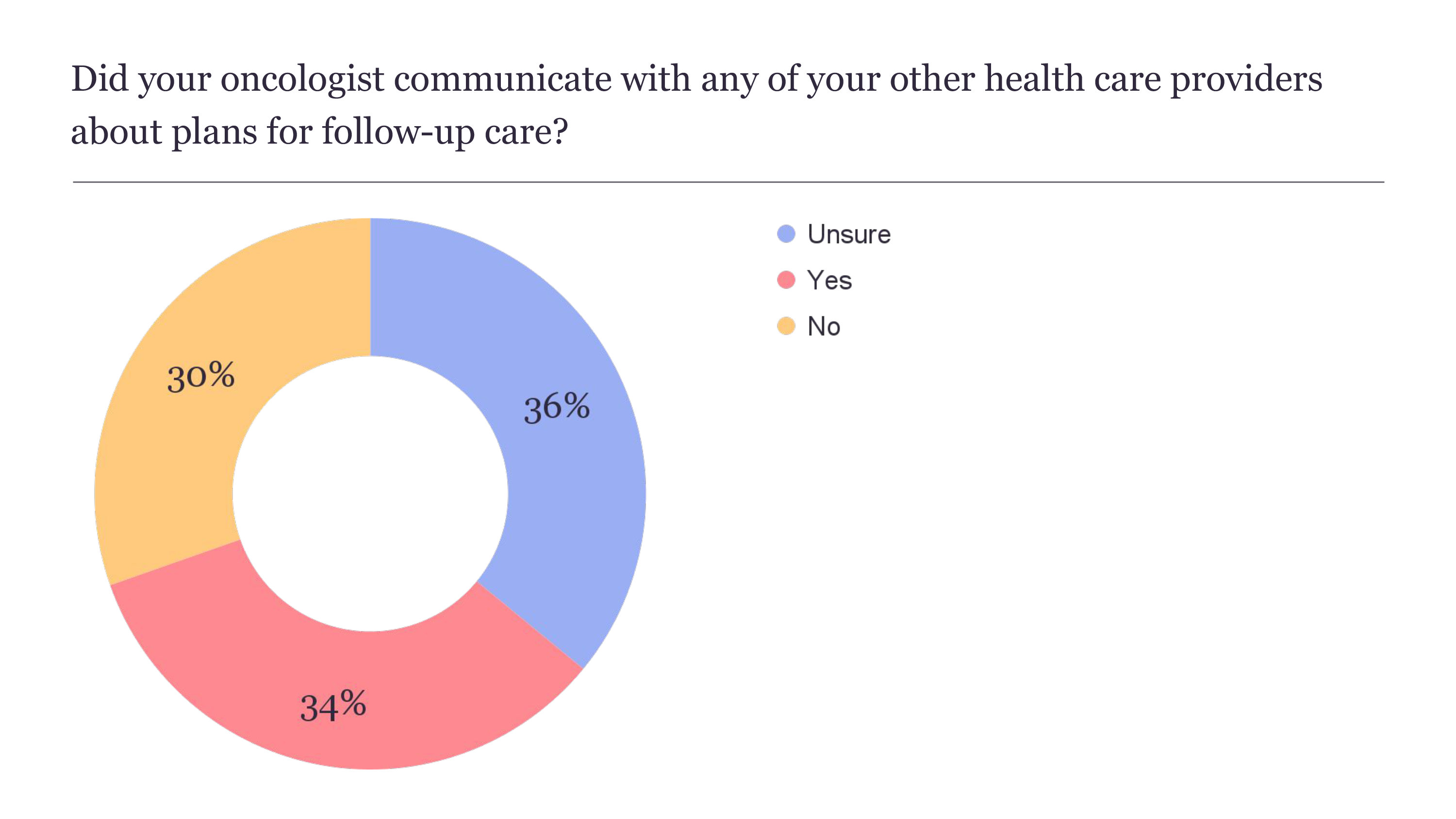

66% said that their oncologist either didn’t communicate with any of their other health care providers about plans for their survivorship care or that they didn’t know if that communication was taking place

Source: Data from a July–August 2023 survey by Breastcancer.org.

Our findings are similar to those reported by the nonprofit National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (NCCS) in its 2022 nationwide survey of people diagnosed with a variety of cancer types. In the NCCS survey, just 45% of respondents felt their health care provider did a good job transitioning them to post-treatment care.

“At the end of breast cancer treatment, some women feel abandoned,” says Julia Rowland, PhD, former director of the Office of Cancer Survivorship at the National Cancer Institute, a member of the board of the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship, and senior strategic advisor for the Smith Center for Healing and the Arts. “They ring the chemo bell and then they’re out the door with no roadmap or plan of action. The message to them is, ‘go back and pick up your life and thrive,’ but we don’t give them the help that they would need to do that.”

Due to advances in early detection and treatment, and because the U.S. population is aging, there are more people living with or beyond breast cancer than ever before. Currently, there are more than 4 million people who are either being treated for or who have completed treatment for breast cancer, according to the American Cancer Society. Figuring out how best to provide care to the growing number of cancer survivors is a major challenge for health care providers and organizations.

Cancer care teams are often spread thin from the other demands of their jobs, making it hard for them to prioritize the care of the patients who are done with active treatment. In some areas of the country, there aren’t enough oncologists to meet demand. And there can be a lack of clarity about which health care provider should lead and coordinate an individual patient’s post-treatment care.

As Anne Courtney, AOCNP, DNP, a licensed nurse practitioner in UT Health Austin’s Livestrong Cancer Institutes and director of the oncology clinic at UT Health Austin, explains, “Right now our health care system unfortunately places too high an expectation for cancer patients, who are already overwhelmed, to navigate a lot of their survivorship care themselves.”

The survivorship care movement

Survivorship care is a relatively recent development; it emerged as a movement and area of research over the past 40 or so years. Pediatric oncologists were among the first to recognize the need to follow their patients after active treatment and help address their ongoing medical, psychological, and financial concerns. Starting in the early 1980s, they established specialized clinics and programs at some cancer centers to care for survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer.

The field of adult cancer survivorship followed close behind, formally getting its start in 1986 with the founding of the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (NCCS), which advocates for policies to improve follow-up care for people of all ages.

Since then, the field has continued to grow, with government health agencies, medical societies, and cancer centers working to develop standards and best practices for post-treatment care:

In 1996, the National Cancer Institute’s Office of Cancer Survivorship was created to promote research on how to better identify and meet the needs of cancer survivors.

In 2006, the Institute of Medicine published an influential report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, that drew attention to the gaps in patients’ long-term care.

Beginning in the early 2000s, many cancer centers and hospitals throughout the U.S. opened clinics and programs to care for adult cancer survivors, with some focused specifically on breast cancer survivors.

But while progress has been made, gaps in care persist.

“There’s a disconnect between the guidelines and the evidence, and how survivorship care gets delivered,” says Patricia Ganz, MD, a breast medical oncologist who is a distinguished professor of medicine and a professor of health policy and management at UCLA, as well as director of the Center for Cancer Prevention and Control Research at the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center. “Doctors still don’t always identify or ask about the post-treatment issues patients are suffering with and don’t know where to refer them for help with those problems.”

What does good follow-up care look like?

According to guidelines from ASCO, as well as the experts we spoke with, follow-up care after active treatment for early-stage or locally advanced breast cancer should include meeting with an oncologist or other health care provider regularly for check-ups that include a physical exam. Typically, this would be two to four times a year for the first five years after active treatment and then once a year after that. The provider or care team should also:

Create a customized breast cancer follow-up care plan, based on an individual’s unique needs, age, diagnosis, and treatment

Monitor for a recurrence or a new cancer (such as with an annual mammogram, if there is remaining breast tissue)

Prescribe long-term treatments (such as hormonal therapy), if appropriate, and help with any side effects or other problems that make it hard to stick with those treatments

Check for and provide therapies for ongoing treatment-related side effects (such as lymphedema, fatigue, peripheral neuropathy, sexual health problems, fertility problems, or depression)

Offer referrals to specialists and coordinate care between health care providers

Offer resources to help with financial concerns, health insurance, disability benefits, mental health, transportation, and other needs

Monitor overall health; make sure the patient is receiving routine/preventive care (colonoscopies, pap smears, bone density scans, flu shots) and provide counseling about living a healthy lifestyle (quitting smoking, eating healthy, exercising, getting enough sleep)

“Survivorship care is actually not that complicated,” says Kathy Miller, MD, professor of oncology and of medicine and associate director of clinical research at IU Health Melvin and Bren Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center in Indianapolis, Indiana. For people with early-stage breast cancer who don't have a lot of complications following treatment, she explains, “it can usually be delivered in two visits per year with a provider who is knowledgeable about breast cancer and breast cancer therapies.”

Most people receive at least some of their follow-up care from an oncology care team, especially if they’re going to be taking hormonal therapy for five or more years. Follow-up care can also be provided by other cancer specialists and by a primary care provider or gynecologist who is knowledgeable about breast cancer.

Follow-up care and health disparities

Good follow-up care matters because it can help ensure the best possible outcomes and quality of life after treatment. It’s important for anyone who has been diagnosed with breast cancer. But the stakes are even higher for some.

Studies show that certain groups, including people who were diagnosed with breast cancer at a younger age, are Black, have a low income, have no insurance, or have public insurance (such as Medicaid) are at higher risk for lacking appropriate breast cancer care and for having worse outcomes. For example, Black women have a 40% higher death rate from breast cancer than white women in the U.S. These at-risk groups may be especially vulnerable to the effects of inadequate follow-up care.

The need may also be greater for people who received more intensive treatment (for example, certain chemotherapy medicines that are more likely to cause ongoing side effects) and those who were diagnosed with a type of breast cancer that is more likely to recur after initial treatment (such as triple-negative breast cancer) or who have a genetic mutation that raises the risk of developing a new breast cancer or other cancers.

Most people diagnosed with breast cancer (up to 80%) have hormone receptor-positive disease and are prescribed hormonal therapy for 5 to 10 years to reduce their risk of recurrence. However, lots of them don’t take the hormonal therapy as prescribed or for the recommended duration of time because of the side effects, the cost, and other factors.

Some of the groups that are already at higher risk for worse breast cancer outcomes for other reasons are also less likely to take hormonal therapy as prescribed. This can put them at greater risk for breast cancer recurrence, metastatic spread, and cancer-related death.

“Hormonal therapies are lifesaving therapies,” says Dr. Ganz. “If someone can’t afford hormonal therapy, doesn’t understand why it’s being prescribed, or if their side effects aren’t being managed, there is a great risk they will stop taking it. And then they have a higher risk of recurrence.”

There are strategies that can potentially help people stick with hormonal therapy, including using certain medications or complementary therapies to ease side effects. In some cases, it’s possible to change the dose or switch to a different type of hormonal therapy medicine that has milder side effects.

But people who are having trouble taking hormonal therapy need to have access to high-quality follow-up care so they can be fully informed about their options. In particular, they need to have good, open communication with a health care provider who listens to their concerns, works to find ways to ease their side effects, and can talk about why it’s worth trying to stick with hormonal therapy. In some cases it may even make sense to stop hormonal therapy, but ideally that’s a decision that a patient and a doctor should discuss and make together.

Barriers to good follow-up care

We asked researchers, doctors, advocates, and breast cancer survivors to tell us which factors most commonly prevent people from getting follow-up care that meets their needs.

Barrier No. 1: Not having a plan

Ideally, when you’re finishing your main treatments for breast cancer, your cancer care team would talk with you about the follow-up care that’s recommended for your situation — and which providers to go to for those appointments. This would help give you clear direction about next steps.

How you get this information, however, is still the subject of some debate.

Many medical and patient advocacy organizations, including ASCO, the American Cancer Society, the Institute of Medicine, the NCCS, and others, recommend that oncology care teams also give each patient finishing active treatment a personalized, written document called a survivorship care plan. The plan is supposed to include:

a summary of your specific diagnosis, the treatments you received, and the potential side effects of those treatments

a plan for follow-up care, with recommendations for the type and timing of follow-up visits

recommendations for tests to check for a cancer recurrence or a new cancer

names and contact information for the doctors on your team

Creating a written follow-up care plan has a few advantages: all the information is in one place, it can be shared among all of a patient’s health care providers (for example, in the patient’s electronic medical record), and it can follow the patient wherever they go (including if they move or are traveling). It may also help clarify which providers will be overseeing each aspect of a patient’s ongoing care.

But some experts we spoke with said that there has been too much focus on survivorship care plans as a specific tool, since a few studies have shown that they don’t improve patients’ outcomes or their satisfaction with follow-up care. They also noted that patients and health care providers don’t always refer back to the survivorship care plan after it’s created — sometimes they file it away without paying much attention to it.

What’s most important is that each patient has a conversation about follow-up care planning with their cancer care team — with or without a written plan.

It can’t be just about a piece of paper,” says Dr. Rowland. “It should be a conversation where the provider talks with you about what happened during your treatment and asks: ‘What questions do you have, what problems do you have, what are you worried will happen in the future and how can we address these concerns?’”

Unfortunately, many people don’t have that follow-up care planning conversation with their oncology team nor do they receive a written plan. Without guidance, they may not know which resources are available to help them during the survivorship phase. They also may not know which symptoms to look out for that could be related to treatment side effects or a potential cancer recurrence.

Barrier No. 2: Not having coordinated care

During active treatment, your oncology care team usually leads and coordinates your breast cancer care and may also help take care of your other health care needs. But when your active treatment ends, it may no longer feel like anyone is in charge. Care may become more fragmented, especially if the providers you’re seeing aren’t all within the same hospital or health system.

“It’s kind of bleak for the average breast cancer patient trying to get follow-up care,” says Amanda Helms, who lives in Alexandria, Virginia, and completed her active treatment for breast cancer in the fall of 2020. She is an advocate on the NCCS Cancer Policy & Advocacy Team. “I was confused about which doctor I should see for what. I found that primary care providers wanted to refer me back to my oncologists and my oncologists wanted to refer me back to primary care. No one discussed if there would be a point that I should fully transition back to my primary care doctor,” she says.

Source: Data from a July–August 2023 survey by Breastcancer.org.

People finishing active treatment are often told by their cancer care team that their primary care doctor should be involved in their breast cancer follow-up care. The idea is that a primary care provider (PCP) can play a key role in coordinating post-treatment cancer care and can more comprehensively address a patient’s health care needs.

“PCPs tend to be much more skilled than oncologists and engaged when it comes to things like managing depression and counseling patients on smoking cessation,” says Dr. Ganz. “And in any case, a lot of patients don’t need to keep seeing an oncologist regularly for their entire life.”

But some people have a PCP who isn’t knowledgeable enough to oversee care related to breast cancer; the doctor may refer them to other providers. And some people don’t have a PCP at all. They might try to rely on their oncologist for preventive care or other general health care that oncologists don’t typically deliver during the survivorship phase.

“Where I live, we have fewer PCPs than ever and so many folks are using walk-in and urgent care clinics and don’t have a relationship with a PCP,” says Rachel Ferraris, a breast cancer survivor in Warner Robins, Georgia, who has worked as an oncology patient navigator and is an advocate for the NCCS Cancer Policy & Advocacy Team. “They fall back on their oncologist because they don’t know who else to call. It’s a big problem that people don’t know who to see for their follow-up care.”

In Breastcancer.org’s 2023 survey, 49% of respondents reported that their primary care provider wasn’t involved in their follow-up care or that they didn’t have a primary care provider.

Source: Data from a July–August 2023 survey by Breastcancer.org.

Another issue is that the various doctors who are seeing a patient for breast cancer follow-up care may not be coordinating well with one another. In some cases, they can’t easily share notes, records, imaging, and other test results. This can lead to gaps in care or duplication of care, with patients having the same test done multiple times by different providers or having more follow-up appointments than are really needed or recommended in clinical guidelines.

Barrier No. 3: Not receiving enough help with side effects

People who’ve been treated for breast cancer often struggle with lingering side effects that harm their quality of life and ability to function. Doctors call the side effects that start months or years after treatment ends “late effects.” Those that begin during or right after treatment and continue for months or years afterwards are “long-term effects.”

The 2022 survey by the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship found that nearly six in 10 cancer survivors diagnosed 10 or more years ago still experience symptoms, with mental health and sexual concerns the most likely to be prolonged.

“I think the biggest problem people treated for breast cancer face in the survivorship phase is not getting enough help with side effects,” says Dr. Courtney. “It can be hard for health care providers to make sure all the secondary effects of treatment are fully attended to.”

Side effects vary in severity and from person to person. Some can be life-threatening if they’re not appropriately addressed, such as heart problems linked to certain chemotherapy medicines, hormonal therapy medicines, targeted therapy medicines, and radiation therapy.

Common late and long-term side effects of breast cancer treatment include:

In the best-case scenario, your doctors would talk with you early on about the possible late or long-term side effects you might experience based on the treatments you’re receiving. At appointments after your active treatment ends, they would work with you to identify any side effects you’ve developed by doing physical exams and tests and asking you about symptoms.

If needed, they would offer options for managing and treating side effects, including referrals to specialists who could help.

However, this level of care and attention to late and long-term side effects — which is recommended in clinical guidelines from ASCO and other organizations — may not be delivered in practice.

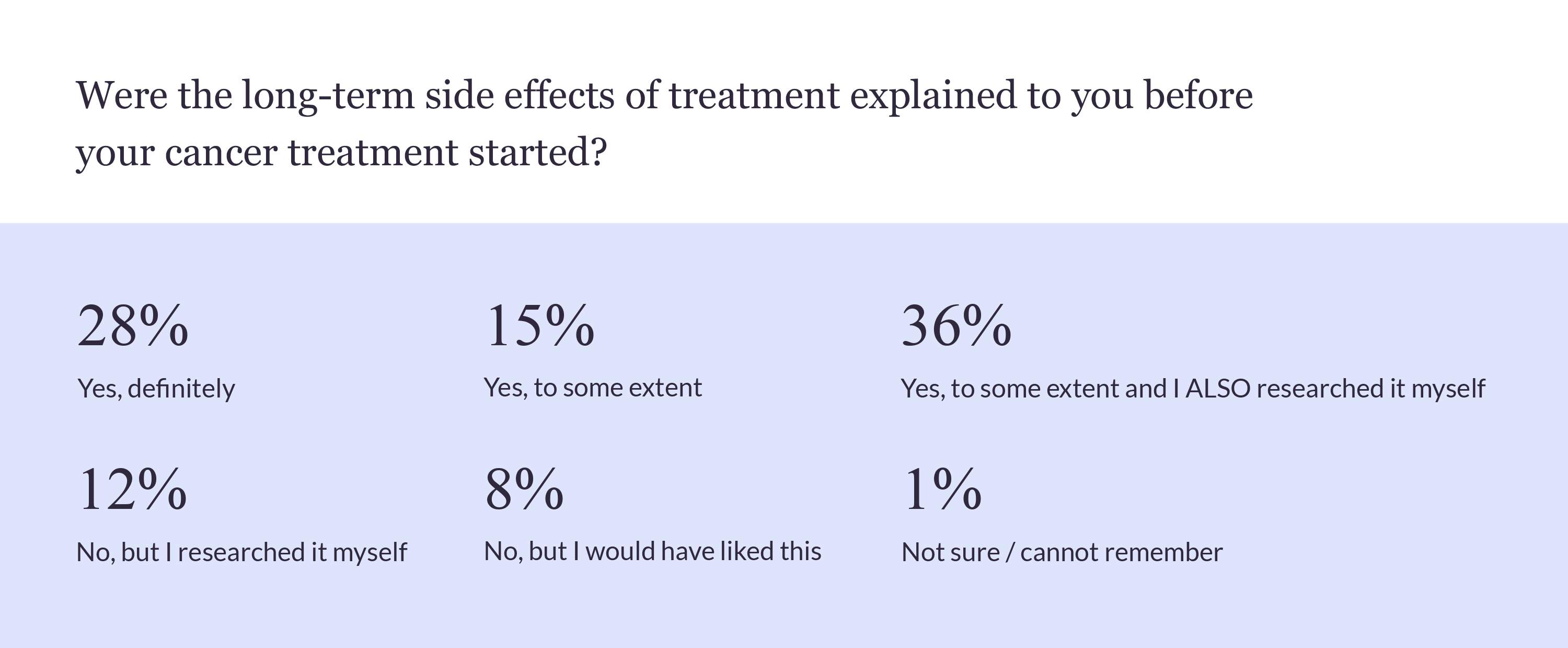

Source: Data from a July–August 2023 survey by Breastcancer.org.

“For most of the side effects, there are very specific interventions that are available and helpful,” says Dr. Ganz. “But the challenge is that doctors don’t always ask about and identify the patient’s side effects and don’t always know about all the interventions and resources to recommend.”

We spoke with people treated for breast cancer who said they weren’t given much information about possible side effects to look out for. One initially thought the swelling that developed around her breast after a lumpectomy was a sign of an infection or of cancer returning, when it was actually lymphedema. Others said that health care providers dismissed their concerns about side effects and that they had to find solutions on their own.

Megan-Claire Chase thought the recommendations she got from her oncologists for managing the neuropathy in her feet — such as to exercise and take a medication called gabapentin — weren’t doing enough to help. Her neuropathy was getting worse and was causing her to have dangerous falls and making it unsafe for her to drive. After several years, she found a chiropractor online who specializes in chemo-induced neuropathy. He was able to help restore some of the sensation in her feet using an electrical stimulation therapy machine and other therapies. “He has given me hope. But I feel like it shouldn’t have been this hard and taken me years to find him,” says Chase.

Like Chase, Amanda Helms also had to be persistent and do her own research to find effective treatments for her side effects. Helms has chemo-induced problems with concentration and short-term memory (commonly referred to as chemo brain). At one point the symptoms got so bad she feared she’d lose her job because of them. She did some research and thought it might be worth trying medication for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) to see if it would help. After consulting multiple oncologists and psychiatrists who weren’t knowledgeable about chemo brain and weren’t willing to try treating her with ADHD medication, she eventually found a psychiatrist who prescribed a non-stimulant ADHD medicine.

“That medication has been life-changing for me,” she says. And even though long-term cognitive deficits are common, affecting more than 30% of breast cancer survivors, Helms says, “I found out that a lot of health care providers don’t know what chemo brain is.”

It’s common for people to have high out-of-pocket costs for the therapies that can ease their treatment side effects. For example, mental health counseling, complementary therapies, physical therapy, and lymphedema treatments and supplies (such as compression bandages and garments) may not be covered or may only be partly covered by insurance. Chase’s insurance only partly covers the expensive visits with her chiropractor.

Lena (name changed to protect privacy) sees a physical therapist who has taught her exercises that have helped make the chronic pain in her arm and shoulder — caused by fibrosis (scar tissue) from radiation therapy — more manageable. Since she finished treatment for invasive ductal carcinoma in late 2021, the side effects have been worse than she expected. “My insurance paid 100% for the breast cancer treatments that did the damage, but doesn’t pay for my physical therapy,” Lena says. “It’s a system that is not focused on your quality of life after treatment.”

Hormonal therapy medications, which are among the most widely used types of breast cancer treatments, can cause troublesome side effects such as hot flashes, joint pain, weight gain, depression, vaginal dryness, trouble sleeping, fatigue, and difficulty concentrating. Some of the less common but more severe side effects of certain hormonal therapy medicines are stroke, blood clots, heart problems, osteoporosis, and endometrial cancer.

Hormonal therapy is typically supposed to be taken for 5 to 10 years after breast cancer surgery. But multiple studies have shown that between 20% to 50% of people who are prescribed hormonal therapy either don’t start taking it, skip doses, or stop taking it early — in many cases due to the side effects. This can increase their risk of recurrence and cancer-related death.

It’s likely that outcomes could be improved if more attention were paid to side effects.

“Some people who have side effects might feel like they have to accept a sexless life, pain, depression, anxiety, or tasks they can’t do,” says Marisa Weiss, MD, director of breast radiation oncology at Lankenau Medical Center in Wynnewood and Paoli Hospital in Paoli, Pennsylvania and chief medical officer and founder of Breastcancer.org. “They might give up at a certain point and accept the fact that their quality of life sucks or at least is not as good as they hoped it could be.”

Recognizing the need for better survivorship care

Advocates say that policy changes are needed to improve cancer survivorship care, expand insurance coverage for it, and make access more equitable.

“It takes time, experience, and adequate insurance reimbursement to develop good survivorship care, and it’s hard to do that with the limitations of our current health care system,” says Dr. Courtney.

Legislation that would address some of the gaps in follow-up care for people who’ve been diagnosed with cancer has been introduced in Congress. Two lawmakers who are breast cancer survivors, Congresswoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-FL) and Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-MN), are among the original cosponsors of the Comprehensive Cancer Survivorship Act (CCSA).

First introduced in Congress in December 2022 and reintroduced in June 2023, the CCSA would create a new billing code that would allow health care providers to bill for the time they spend developing survivorship care plans — and on other cancer care planning and coordination – for people with Medicare. It would also provide coverage of fertility preservation services for people with Medicaid who are undergoing cancer treatments that could lead to infertility and would establish new research projects and programs aimed at improving survivorship navigation and care.

A separate proposed bill, the Cancer Care Planning and Communications Act (CCPCA), would just create the new Medicare billing code for care planning and coordination.

Other recently passed bills are helping to close some gaps, such as the Lymphedema Treatment Act, which requires Medicare to cover certain compression garments and other supplies for treating lymphedema starting in January 2024.

Dr. Rowland says that she feels both optimistic and frustrated about the state of survivorship care. “We have a very broken medical system. If we had a single payer system it would be easier to deliver survivorship care,” she says. “But at the same time, we now have so many cancer survivorship resources we didn’t have before. That makes me wonderfully optimistic about patients’ outcomes. The challenge is: How do we help people access those resources when they need them?”

Today, it often falls on patients to find resources and care. And when they do, it may be at a later point in their survivorship than would be ideal.

Melissa del Valle Ortiz, who lives in Brooklyn, New York, and completed active treatment for breast cancer in 2021, says she wishes oncology teams would offer information and referrals for mental health concerns as a standard part of treatment right after diagnosis. She had to find a counselor on her own when she became very depressed after finishing active treatment. Her severe depression seemed to be, at least in part, a side effect of taking tamoxifen.

“I wish it was a requirement that they tell you about mental health symptoms to look out for and give you a referral for counseling early on,” says del Valle Ortiz. “No one on my treatment team ever had a conversation with me about mental health.”

One of the reasons the end of active treatment for breast cancer can be a challenging time is that what you’re going through in that phase may not be immediately obvious to others. Several people we spoke with who recently finished treatment said that they feel like everyone expects them to move on and return to normal. Friends, acquaintances, family, work colleagues, and even some of their health care providers don’t seem to understand the extent to which they are still grappling with difficult physical and emotional changes stemming from their diagnosis and treatment.

“The people around you — including the people who love you — just want it to be done and for you to be OK. But it’s not done,” says Kate Rosenblum of Ann Arbor, Michigan, who completed a year and a half of treatment for breast cancer in the spring of 2023. “When you’re in the process of healing, the path is not clear. It feels like a bomb dropped on your life.”

This content is supported in part by Lilly, AstraZeneca, Biotheranostics, Inc. A Hologic Company, Pfizer, Gilead, Exact Sciences, Novartis, Seagen, and MacroGenics.