New Research Links Aggressive Breast Cancers to Superfund Sites

Updated on January 29, 2026

In the summer of 2024, Erin Kobetz, PhD, MPH, sat in a South Florida church as she listened to community members’ concerns that a nearby air force base was to blame for higher rates of breast cancer in their community. The airbase was declared a federal Superfund site in 1990. They wanted Kobetz’s help.

Superfund sites are shuttered sites — often mines, landfills, or manufacturing plants — in the U.S. with toxic chemical waste that was never properly managed. This waste includes environmental pollutants that can be carried by air and/or water. From there, they can make changes in the body that increase the risk of diseases like breast cancer.

Kobetz, who is a public health researcher, studies cancer disparities and community outreach with her team at the University of Miami’s Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center. Their new research suggests that people living near Superfund sites have a higher risk of developing triple-negative (TNBC) and metastatic breast cancers compared to other types of breast cancer.

Sites polluting the water and land

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has been cleaning up hazardous waste dumps through the Superfund program since the 1980s. The agency assesses sites, adds the worst ones to the National Priorities List, and then coordinates their cleanup.

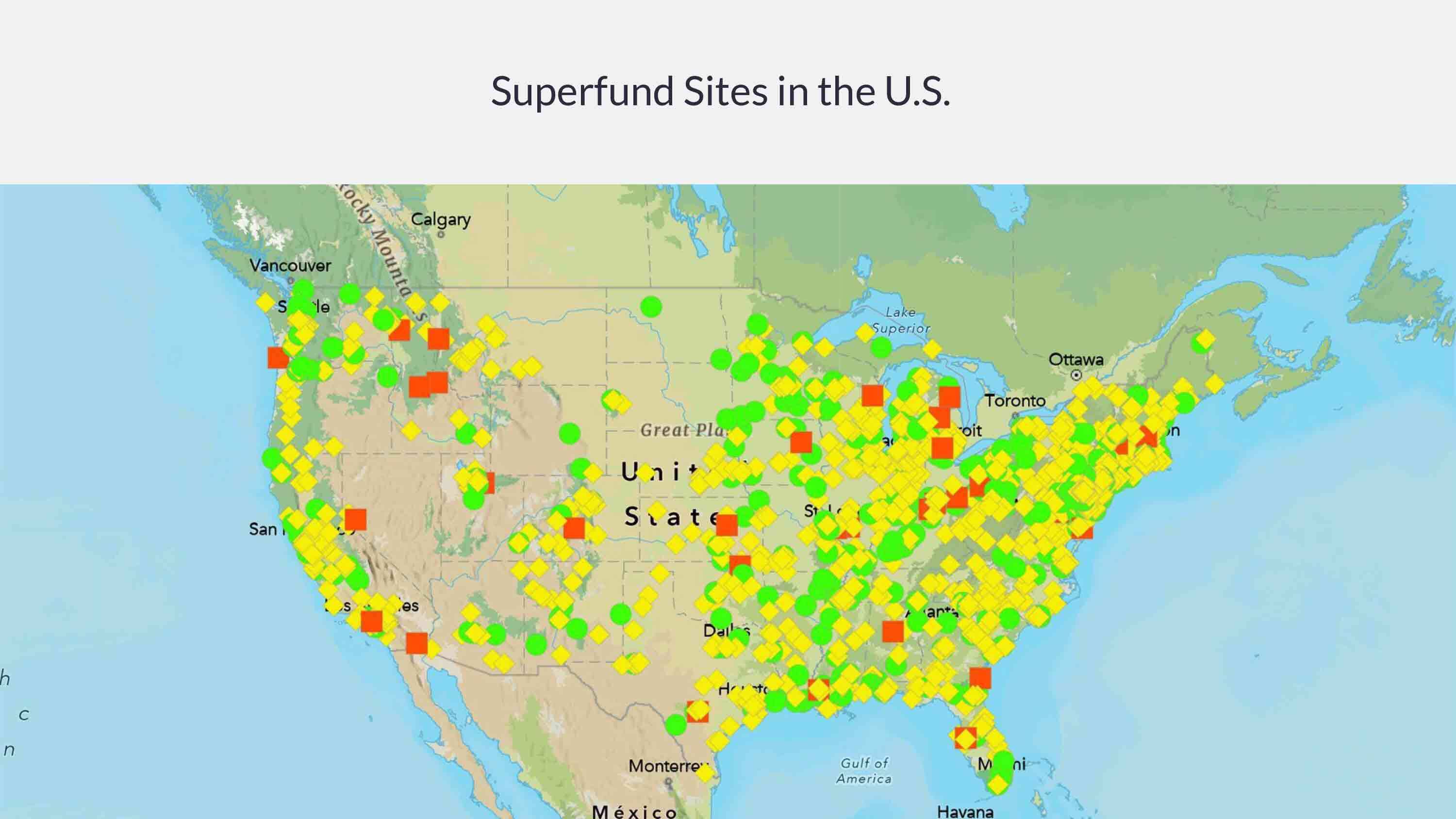

A map showing Superfund sites in the U.S. Yellow are current Superfund sites; Green are deleted (and cleaned up) Superfund sites; Red are proposed Superfund sites. Sources: Esri, TomTom, Garmin, FAO, NOAA, USGS, © OpenStreetMap contributors, and the GIS User Community, Esri, USGS

“Sites get added to the National Priorities List because they are found to have very high contamination levels of chemicals that are known to be dangerous to human health,” says Jennifer Kay, PhD, a research scientist at the Silent Spring Institute, a nonprofit that studies the links between chemical exposures and breast cancer.

Some Superfund pollutants have been tied to breast cancer directly, like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and certain organic solvents. Other pollutants act as hormone disruptors that may increase breast cancer risk, like phthalates.

Women living within 4 miles of a Superfund site had a 27% higher chance of being diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer.

These pollutants can spread into nearby communities through air, water, and/or soil. Often this happens through groundwater, water beneath the surface that provides drinking water for some people, Kay says. “Chemicals will seep down through the soil, get into the groundwater, and be carried into the community.”

There’s a lot that researchers don’t know about how this environmental pollution affects breast cancer risk. But because certain breast cancers are on the rise, especially in young people, experts are trying to find out what’s behind them so new cases can be prevented.

Living near a Superfund site: The research

For the new research, Kobetz focused on the 12 Superfund sites in the South Florida area, once home to recycling centers for electronics and metal, dry cleaning shops, and manufacturing sites.

In her first study, she looked at nearly 22,000 cases of breast cancer in the region. About 10% of people lived near a Superfund site. Kobetz wanted to know if women who had metastatic breast cancer (cancer that has spread beyond the breast) when they were first diagnosed were more likely to live in certain areas compared to women who had nonmetastatic breast cancer. She found higher rates of metastatic disease in women who lived near Superfund sites versus those who lived further away. Women living within 4 miles of a Superfund site had a 27% higher chance of being diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer.

These findings got her team thinking about triple-negative breast cancer, which is the most aggressive form of breast cancer and tends to be diagnosed at later stages. In a follow-up study of over 3,000 women, they found that women with breast cancer living close to a Superfund site (1,410 women) had a 33% higher chance of being diagnosed with TNBC compared to those who lived further away.

Kobetz hopes that research into Superfund sites may help explain why Black women have three times the risk of developing triple-negative breast cancer compared to white women. People of color are more likely to be exposed to hazardous chemicals from Superfund sites. “There’s this persistent issue of disparities,” Kobetz says, “and we need to think creatively about what’s causing that and what do we do about it.”

Next steps: Superfund sites and breast cancer risk

Kay, who wasn’t involved in these studies, is curious how living near Superfunds impacts breast cancer risk more broadly. She wonders: Are people who live near Superfund sites more likely to get any type of breast cancer than those who live further away? Kobetz hopes to answer some of these questions in the future.

Kobetz says the next part of this project will be figuring out how people are being exposed to pollutants from Superfund sites and which ones have a stronger link to breast cancer risk. So far, she knows many of the pollutants are hormone disruptors, but her team doesn’t yet know which pollutants are the most common. They plan to study the chemical compositions of the Superfund sites and collect new data from participants over time to study breast cancer risk in a more focused way.

Protecting people at high risk

The best thing to do to protect communities surrounding Superfund sites is to clean up these hazardous sites, but that can often take decades. Of the 1,802 Superfund sites, only 458 have been fully cleaned up. This process is likely to get more challenging for the EPA: The agency may soon face a 23% budget cut from a spending bill passed by the Republican-led House of Representatives subcommittee focused on the environment. And the Trump administration is on track to fire 1 in 3 EPA employees by the end of 2025.

Kobetz’s research is still in the early stages, but she hopes her work can one day inform policy and practice around reducing the risk of breast cancer. In the meantime, she says, “all women should take breast cancer prevention and early detection seriously, particularly if they live near a Superfund site.”

If you’re one of the 73 million Americans living near a Superfund site, there are several steps you can take to reduce your exposure to pollutants:

For polluted drinking water: Install a filter on your tap or use a pitcher with a filter. To find the best water treatment for your home, check out this resource from the National Sanitation Foundation.

For polluted air: If your outdoor air is heavily polluted, keep your windows and doors closed and use an air purifier with a HEPA (high-efficiency particulate air) filter to keep your indoor air clean.

For polluted soil: If your soil is contaminated from a nearby Superfund site, avoid gardening since chemical pollutants can take hold in fruits and vegetables, increasing your risk of exposure.

If you have specific questions or concerns relating to living near a Superfund site or the clean-up status of a nearby site, you can contact EPA Community Involvement Coordinators or Remedial Project Managers by searching for a Superfund site on the EPA website.